Originally published in Medium

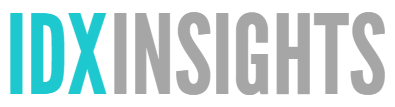

In their seminal 1992 paper, Eugene Fama and Ken French identified two new “alternative” factors that helped explain the excess returns of certain stocks beyond what the traditional “global market portfolio” used in the CAPM model. These new “factors” were “Value” (as defined by Price/Book ratio) and “Size” (based on a company’s market cap). Despite the fact that the idea of “Value” investing certainly wasn’t new (Ben Graham’s Intelligent Investor was published in 1949), Fama & French’s research kicked off an explosion in the search for new factors that could explain (and thereby potentially capture) excess performance. This has resulted in a subsequent explosion in “Smart Beta” ETFs:

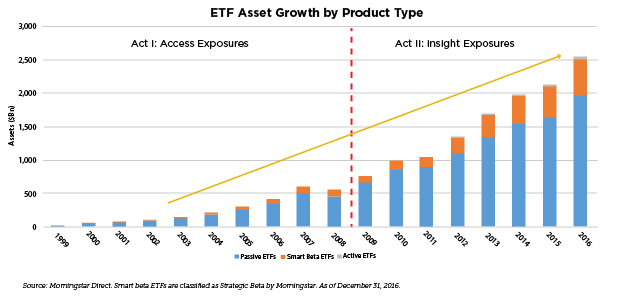

Generally this is a very favorable development for investors (both retail and institutional) in that the investing landscape (specifically the domain of active “alpha” managers) is becoming democratized (as shown by the graphic below). This has allowed investors to access the same factors underlying active managers’ returns in a simple, cost-effective and transparent format. Depending on the sophistication of the model, smart-beta ETFs can even be effective in replicating certain hedge fund strategies entirely.

Not All Factors are Created Equal

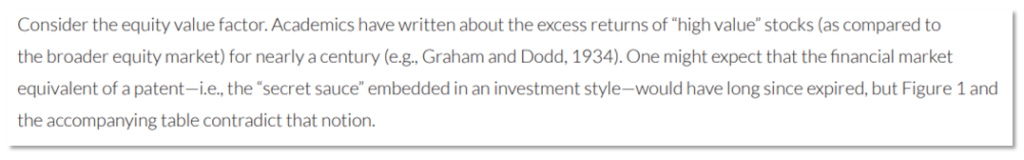

While this “commoditization of alpha” has been good for investors (and a driving force behind the “Active to Passive” migration), it’s also seemed to cause many investors to assume that the “Value” factor (for instance) is a homogeneous building block that can be swapped in and out of a portfolio without concern….just find the cheapest ETF and you’ll be fine. Two Sigma addresses this issue in a recent paper:

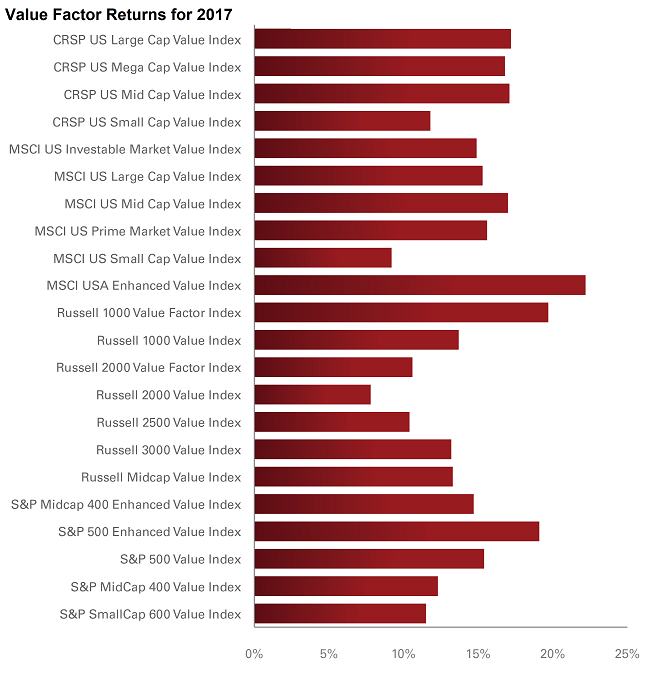

Clearly the Value risk factor can vary greatly depending on how its (i) defined and (ii) how it’s constructed.

While Fama and French often get credit for “discovering” the Value (and Size) factors, it was by no means a new idea that they created. Benjamin Graham (the true “godfather” of Value investing) had already published an entire book about the subject decades prior. Fama & French just used a relatively simple definition of value that looked at a company’s book value to market cap. The value factor they created was known has “High Book-to-Market minus Low Book-to-Market” (HML). This factor was created by taking the average equity returns of the top 30% of high book-to-market equities and subtracting the average returns of the bottom 30% book-to-market equities.

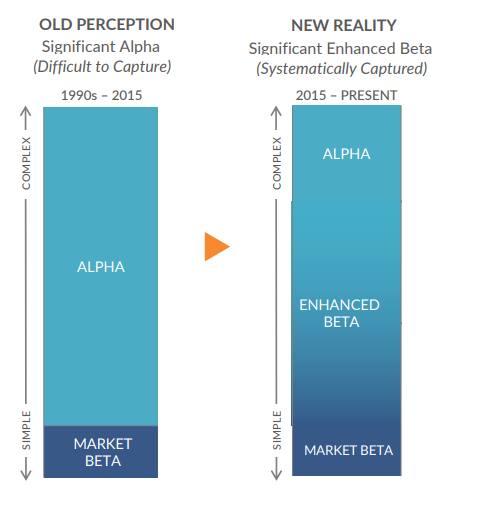

As pointed out by Two Sigma, “The Fama-French (1991) results raise numerous questions among academics and practitioners. One such question is whether the book-to-market ratio represents the most efficient way to garner exposure to the value risk factor. For example, why not sort firms by earnings yield or cash-flow yield instead?”

They go on to illustrate the rolling correlation of expected returns for 2 different (but popular) definitions of “Value”: Book-to-market and Earnings Yield:

Clearly, how one defines “Value” matters. As shown in a recent article by Vanguard, the variations in how value (for example) is defined and implemented can have meaningful impacts to performance:

Implementation: Theory vs. Practice

The obvious question becomes “What’s the RIGHT way to define & express a factor?” This question becomes even more important once more than one factor is taken into account. To explore this further, we’ll consider the example from Fama & French’s seminal paper: Small Cap Value. These 2 factors are probably the most popular within the “Smart Beta” landscape and since that 1992, hundreds of smallcap value funds (active and passive) have launched. To examine these factors further, we’ll look to the firm where Eugene Fama is a director, Dimensional Fund Advisors (DFA)…and specifically the DFA US SmallCap Value Portfolio (DFSVX).

From reading the prospectus, two things immediately stand out:

“Securities are considered value stocks primarily because a company’s shares have a low price in relation to their book value”

and…

“the higher the relative market capitalization of the U.S. small cap company, the greater its representation in the Series”

So, this fund is implementing the smallcap value factor in a very similar fashion outlined in the original Fama & French paper by primarily using book value as the signal for “value”. Also of interest is the fact that the fund is then weighting the stocks according to market capitalization (which has numerous known drawbacks).

While there certainly isn’t a “right” or “wrong” way to express exposure to the value factor (or any risk premia for that matter), investors should understand the risk (both direct and indirect) that they’re underwriting when choosing a certain implementation. Relying on a single metric to define value, for example, increases the risk that that exposure may demonstrate extreme deviations from other definitions of value (as evidenced in the chart above). Similarly, the choice to weight companies by their market cap will introduce a momentum tilt that can overwhelm the value effect during certain periods (prominently on display in 2018 among the “FANG” stocks). In either case, these risks/tilts may be perfectly acceptable to the investor – the point to be made is that they represent risks specific to this implementation of the smallcap value factor…not necessarily the factor itself.

Let’s consider another implementation of smallcap value using the Invesco S&P 600 Pure Value ETF (RZV). This ETF still seeks to harvest the smallcap value premium but does so in a different way:

“Value is measured by the following risk factors: book value to price ratio, earnings-to-price ratio and sales-to-price ratio.”

and…

“stocks be weighted in exact proportion to their Style (Value) Scores”

This implementation is diversifying the “model risk” by considering 3 measures of value and then is weighting according to those measures. Also (and importantly) the universe of smallcap stocks has already been screened for profitability (the S&P 600). This is particularly interesting because profitability (or “quality” more broadly) has been shown in numerous academic (and empirical) studies to be a robust “conditioning” factor that can actually enhance the “classic” factor premiums (such as Value).

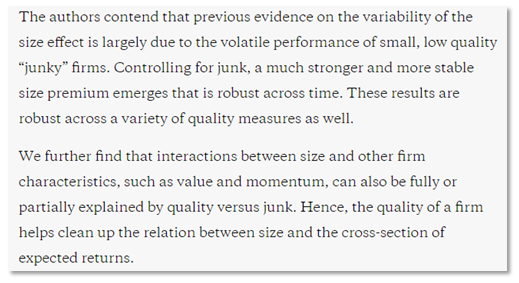

AQR highlights the importance of controlling for quality when evaluating the small-cap premium in a 2015 paper called “Size Matters, If you Control Your Junk”:

In fact, in a 2014 paper, Fama & French revisit their old 3-factor model (which highlighted the “Size” and “Value” factors) and introduce 2 new factors: “Profitability” and “Investment”. Interestingly, they find that once these factors are taken into account “Value” matters much less:

So the Invesco S&P 600 Pure Value ETF (RZV) filters the universe of smallcap stocks for profitability, ranks them according to 3 metrics of value and then weights them according that value “score”. Intuitively, this implementation actually seems to address some of the potential shortcomings of the DFA version.

The Invesco implementation also seems to better align (intuitavely) with the type of value exposure that active managers are harvesting…but in a rules-based fashion (and therefore insulating against all of the issues with discretionary active managers’ decisions)

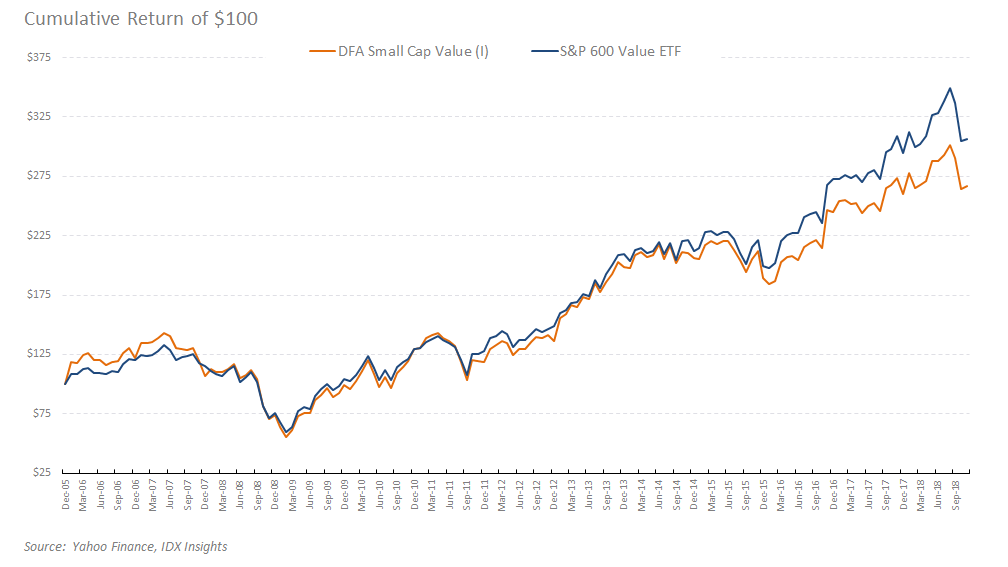

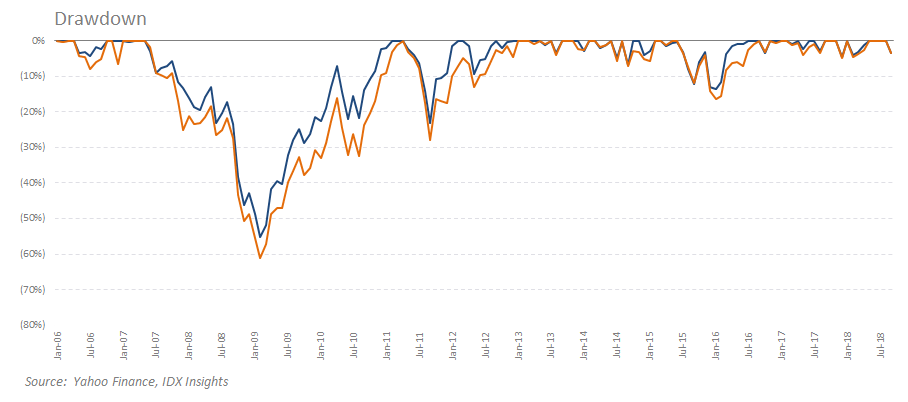

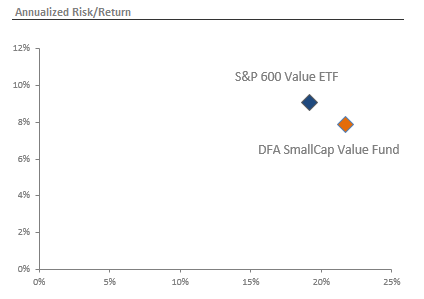

So, how do the two versions compare?

So, over the last 12 years, the S&P 600 Value ETF has sought to extract the same smallcap value premium as the DFA fund but has done so with lower volatility, lower drawdowns and higher returns (after transaction costs & fees).

Both would be considered “Smart Beta” but we would argue one uses a “smarter” approach than the other.